Coming out in midlife, because it’s never too late to be who you really are

Thirty years after shame sent me back in the closet, there is freedom, and rainbows.

I just celebrated the hell out of Pride 2023, the first June that I have felt fully out as a queer woman. Also, I am 52 years old. Coming out in midlife — to family and friends, colleagues, communities, and most of all to myself — is an ongoing process, and this year, with a new relationship, home and growing community of queer friends, felt like a meaningful milestone. The daily news of escalated attacks on queer and trans folks across the United States made honoring queer protest, revolution, and joy extra important to me this year.

Gen Z is pushing the numbers of LGBTQ+ adults higher, with about 19 percent identifying as queer, per a recent Gallup poll, and millennials not far behind. In my GenZ+ bracket, though, our big gay numbers are significantly lower.

Put it this way, if I had known in 1987 that the word “queer” could be anything but a slur, I would potentially have been much more clear on my identity and saved myself decades of furtive bookstore browsing, lurking in the library stacks, and web searching later on.

The ’80s were not queer-friendly

Coming out later contrasts with the age when most of us seem to first sense that we’re not straight. Per a Pew Research study, 12 years old is the median age for that realization, and 20 years old is when we’re first likely to tell family and friends. Some of us have a bigger gap between that realization and disclosure.

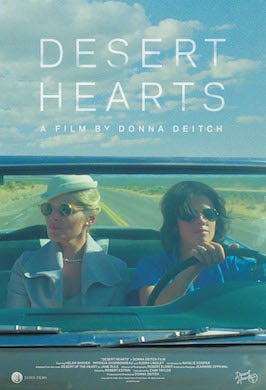

For this sheltered ’80s kid, I simply did not have the language for what I felt, or, more importantly, knew I was not supposed to feel. I know now that what we blew off as “girl crushes” were just crushes. I obsessively watched Jo in Facts of Life reruns for a reason. And some of my Gen X queer peers may relate when I say I simply failed to return the VHS of Desert Hearts to Blockbuster. Our media was lacking, but what did exist made a clear impact, even if we didn’t discuss it.

My loved ones always called me a late bloomer, completely unaware that I had an intense, chaotic, yet deeply loving relationship with a classmate at my all girls Catholic high school that began when I was 15 (I met her in drama club, of all places. Talk about foreshadowing.) That experience ended, abruptly, with her sudden marriage to a man, right before I went to college.

Before that curveball, my beloved high school English teacher discovered us kissing in her empty classroom at lunchtime. I was Mrs. S’s grading and tutoring assistant, thrilled when she gave me a copy of Leaves of Grass (Walt Whitman: super gay!) along with a shiny medal at the sophomore year-end awards assembly. I did way more than blush when she caught me with my girlfriend, and hurt deeply when she never spoke to me again.

The awards dried up, my shame spiral got way bigger than my late-80s bangs, and back into the closet I went — for 24 years. From my 20s to the age of 40, I exclusively dated cis men. My few relationships were short-lived, ultimately unsatisfying, and distinctly non-committal – a state I blamed on my partners, but that, looking back, equally applied to me.

I also started drinking more, and a lot. My next queer relationship, just after my 40th birthday, coincided with a near-deadly skid along my deep alcoholic bottom. As confused and miserable as I was about my life and myself at the time, I knew deep down, even in a fraught and unhappy situation, that this connection with a lesbian who had been out for many years made sense to me in ways that my relationships with my cis man partners never had. I was far from happy and several years away from peace, but I knew a critical course correction when I felt it.

I ordered Lisa Diamond’s Sexual Fluidity, an important book in the limited literature about shifts in attractions over time, kept it on my shelf years before I understood how it translated to my life.

“Sexual fluidity is defined as a capacity for situation-dependent flexibility in sexual responsiveness, which allows individuals to experience changes in same-sex or other-sex desire, over both short-term and long-term time periods,” Diamond writes. “The existence of sexual fluidity does not imply that everyone is bisexual, or that sexual orientation does not exist. Rather, it indicates that sexual orientation does not rigidly predict each and every desire an individual will experience over the lifespan.”

Melissa Giberson, who wrote the upcoming memoir Late Bloomer (pre-orders available now) about coming out at 44, felt similar shifts and ambiguity in the process.

“Never having had a same-sex attraction before I was 44, I had many questions and uncertainties as to what was ‘happening’, she said, adding that she shared some of my concerns about the future.

“Early in the experience, I witnessed a lot of confusion and uncertainty from the women I was interacting with,” she said. “Even if someone’s situation isn’t entirely fulfilling, it’s still familiar and many times it’s the fear of the unknown that keeps people from making changes.”

Isn’t one terrible adolescence enough?

The rest of my 40s focused on getting sober, and dating just didn’t seem to fit into that intense healing process. I identified as queer or bisexual if it came up in conversation, but that was as far as I could go. Still deeply single and feeling like a person with no country where my sexuality was concerned, I frequently joked that I “identified as sober” – partially because I felt that way, and also because I felt like an imposter, and self-deprecating humor is my go-to coping mechanism. If I didn’t have a partner, what difference did it make to anyone who that partner would be if I did? It was easy to cosplay an ally with ambiguous identity, and to keep that closet door mostly closed, if there was no one sharing it with me.

Besides, what do you even do to cope with what can feel like a second adolescence in a 40-something year old body?

“Some of the primary factors associated with adolescence are the pursuit of new experiences, the drive for adventure, increased curiosity about ourselves and the world around us, and immense personal growth and discovery,” says Sex Therapist Dr. Elyssa Helfer. “These factors are essentially mimicked in those who are coming out later in life, and this is often because our position in the world, particularly in our relationships, is shifting.”

The truth is that all of this shifting was terrifying, and I didn’t have a therapist. What I did have was a solid recovery community and a few close ally friends, and that helped in the meantime.

“My recommendation to anyone on a similar path is to find support and diversify it,” Giberson said. “A good therapist who is well-versed in LGBTQ-related issues is a must. I benefited from support groups with other ‘late-bloomers’ and I became friends with women who were traveling the same path and communicated with women who were on the other side.”

That last part was key for me. I had a few already-out queer friends who supported me, and reassured me that my timeline was just fine. They were my first queer community, and remain in my inner circle today. Dr. Helfer echoes the importance of this support system.

“Seeking community is vital for those who are coming out later in life, particularly connecting with individuals who hold similar identities,” she says. “Finding these spaces can open up the door to connection, friendship, and community.”

It’s true: I would have been lost without my people. Because I was also learning to feel feelings for the first time in my adult life, and it sucked. A deep connection with a lesbian friend in recovery at nearly two years of sobriety felt as devoted as a partnership in so many ways, and I wasn’t sure why, but I knew I was in it for the long haul. She knew I was queer, but the relationship wasn’t sexual, and only mildly romantic in the sense that we cared for each other deeply. But after she died by suicide in 2016, I grieved like you might for a lover who wasn’t your lover, but whom you truly, unconditionally loved. We say “love is love”, and all kinds of love have helped me understand myself along the way to coming out.

"Platonic love is more than just friendship," says Jillian Amodio, LMSW, of Moms for Mental Health in Annapolis, Maryland, validating an experience I could never quite find the words for. "This type of love is quite intimate and deep in its own way. Many people find that words like ‘friends’ are simply inadequate when it comes to expressing the depth and value of their closest nonsexual relationships.”

I know now that that relationship was perfect as it was. It helped me accept my identity, and prepared me for deeper partnership. And the more involved I am with LGBTQ+ community, the more I experience loving relationships of all kinds. This commitment to deep friendships and chosen family is one of the many beautiful things about us. I would be lost without my people, whether it’s the stupid memes we send each other all day long or their couches I can sit and cry on, and also watch terrible reality TV.

“Platonic relationships are almost like a type of soulmate, a person who completes or complements you in some way, a person who you love dearly, confide in and have total trust in,” Amodio said. “These relationships allow us to express our human desires for connection, acceptance and love."

Finding freedom in queer community

I met my current partner nearly two years ago, in the queer recovery community. I found my way there more fully after COVID lockdowns opened up, and I realized I needed to face my fear and move into more LGBTQ+ spaces, or risk never doing it at all. After over a year of close friendship, during which I talked myself out of a possible relationship with him due to our age difference (I’m too old!) and my cis-ness (he is a trans man), he stepped up and told me that, labels and differing identities that did not matter to him aside, he’d like to give this a shot.

It helped that he asked me to take a walk on the beach to have this conversation. Game knows no specific age, gender or sexual orientation, it turns out.

Since I began that process, and found not only a supportive significant other, but a group of friends walking similar paths, I have written more, talked more, felt more, and experienced more of myself as a member of the LGBTIA+ community than ever. While I had a full experience of life as a single person and was not even looking for a partner, to walk through life with a loving and committed human at all is cool. To do this with someone who is also committed to growth both inside and outside of their queer identity brings extra meaning and support.

It can also be exhausting, and scary. And it is not lost on me that I could best face these life transitions after a year of work with an amazing trauma therapist, who helps me understand my responses to a complex life transition.

“Fear can be associated with coming out at any age; however, there are unique experiences that exist for folks above 40 that may not exist for those in adolescence or young adulthood,” Dr. Helfer says. “Many folks over 40 have children, are married or partnered, have established careers, long term friendships, and are integrated into social circles and communities. For folks with these types of connections, to open up and come out may shatter expectations or previous perceptions of them, which can prompt a variety of reactions.”

After years of fairly ambiguous orientation and relationship status, I chose to share more specifics about my identity and my relationship with my immediate family, and a few close ally friends. I wanted to be more comfortable expressing myself publicly, and although I was solid in my choices, it felt important to me to involve my closest people. Luckily, most of the reactions were supportive, potentially because I specifically chose to keep my circle of trust fairly small. There are some people I don’t need to talk to about this, yet or ever, and that’s okay.

“First and foremost, those who are coming out later in life get to choose who they come out to, how they come out, and most importantly, IF they come out,” Dr. Helfer says. “Many folks have not earned the right to sit in the vulnerability it often takes to open up about someone’s sexual and/or romantic identity. The discrimination of erotically marginalized individuals and the subsequent harassment, hatred, and violence that can and often does exist plays a major role in whether or not folks feel safe coming out. Physical and emotional safety are crucial for coming out to be considered, and I certainly recommend that folks make decisions with that in mind.”

Glennon Doyle shared on the We Can Do Hard Things podcast and in her bestseller Untamed about her relationship with wife Abby Wambach, and her mom’s initial fear-based reaction.

“This fear that you have is your problem,” Glennon said. “And so I need you to go on your own and figure out this problem that you have, which is your fear, right? And when you are ready to, when you’ve worked out that problem and you are ready to come to our family with nothing but respect and joy and celebration, then we will lower our drawbridge for you. But not one second sooner.”

Doyle’s family is supportive now, and I like to think that that kind of initial boundary-setting helps everyone involved in the long run, to achieve clarity, if nothing else.

Giberson recommends that everyone involved in these coming out conversations simply take their time.

“Patience helps,” she said. “Patience on the part of the person going through the transition and patience for their family and friends who are just finding out about it and might need time to adjust.”

Giberson also echoes my most specific request, which is to take the person coming out to you at their word, that they know themselves and their situation.

“‘What isn’t helpful is asking, ‘Are you sure?’” Giberson said. “Someone coming out has been asking themselves all kinds of questions, likely before they shared it with anyone else, or have been working with a therapist to address the questions. If someone trusts you to share this important information, don’t throw a wrench in all their work and the courage they had to find to tell you.”

Late or early, I am ever grateful that I have the opportunity to live more as myself than I ever have.

“It can be thrilling to see a future with possibilities that one may have never considered,” Dr. Helfer says. “When our canvas is blank, there are no limits to what we can create, and this freedom can influence a new perspective on life.”

Today I see so many possibilities, both because of and besides my bisexual, queer identity — words that mean something to me now, but could change tomorrow, and that’s not just okay, it’s amazing. Today, at 52, I feel free.

Laurie is the managing editor of The Midst, and a writer, editor, photographer, and community builder who lives and works in the DC suburbs with her partner and her puggle, Hoover. An original contributing editor and Voice of the Year at BlogHer, and longtime Communications and Community Director for Mom Media’s Mom 2.0 community, her publishing credits include BlogHer, TueNight, Huffington Post, and Jumble and Flow. Find her at Oh My Dog, LaurieMedia and @lauriemedia and @hooverthepuggle on Instagram. Get in touch at lauriewhite@the-midst.com.

Thank you so much for writing this. As a 49-year-old queer woman (who didn't even kiss another woman until I was 40!) who is finally getting the chance to live life as my true self, your writing deeply resonated with me. I keep worrying that it's "too late." Intellectually, I know it's not and would never tell anyone else that. I've been out as bi for several years to close friends (and have had several one-off experiences with women), and have a fairly large circle of queer people in my life, but lived my entire adult life with cis-male partners. I'm finally flying solo and have a lovely lady in my life (we also have a decent-sized age gap!) who's already showing me it's not too late. Next up: Coming out to my immediate family... Why is that part so tough?

What a generous glimpse of your journey to freedom. Thank you for sharing it.