When your dad's a jerk, is it OK to accept his love?

My dad was an abrasive, unaware, selfish jerk, but that was only one side. Did his loving side count too?

Before I was old enough to complain about my own parents, I heard boomers complaining about theirs. Resentments they harbored for decades started coming out when I was a kid in the 80s. Most boomers I knew seemed unhappy and upset about their childhoods — even the ones who had it pretty good as adults. Like the Thirtysomething ones I watched on TV.

During grandparent visits, I watched their terse interactions, often passive aggressive. I wonder how often loud, expressive All in the Family-style arguments between boomers and my grandparents’ generation really happened in the ‘70s. Every boomer I knew left their parents’ home as a teen, and the parting seemed mutual.

Forget waiting decades, I thought. My thoughts and feelings are gonna come out in real time. Just like I saw on TV talk shows. I’m gonna express myself. Get real. And say it straight up.

Being a GenX brat seemed better than turning into a disgruntled boomer.

The problem was every out loud feeling was buried under attitude. My vulnerable feelings were covered-up to the point I didn’t even really know what I was feeling anymore. So I still ended up with a shitload of repressed feelings about my dad when he died suddenly 15 years ago.

My dad’s other side

No parent is perfect. Learning that is part of growing up. And accepting that is becoming a grown up. But still, the process isn’t easy — especially with some parents, and maybe not even possible with others.

My dad did the fun stuff well. He loved taking my three brothers and me out exploring Chicago, bringing his touristy vibe — and 35 mm Kodak camera — anywhere he went. Super extroverted, always engaging with questions, jokes, and stories. And super physical too, teaching us sports, fun-wrestling with us, and making us feel taller high up on his shoulders.

I always knew dad loved me. But accepting his love was always hard … because of his other side.

If you fell down, dad would give you a swear-word version of “I told you so” rather than comfort. If you dropped your 49 cent hotdog on the floor of a 7-Eleven, he wouldn’t buy you another. If you got a good grade, he didn’t care unless you outscored the rest. The harshness was the point. And the point was to make us winners — and make him look good.

My dad was an abrasive, unaware, selfish jerk. A sharp contrast with another man in my preschooler life: Mr. Rogers. This man told me I deserved to be treated better than how my dad treated me and my brothers. And because I spent a lot of time in and out of other kids’ homes on my block, it seemed like most kids deserved to be treated better too.

Boomer parents didn’t seem to know what the hell they were doing. They did every don’t-do thing I was learning about. Being a “brat” made sense.

A GenX brat: I’ll do it my way

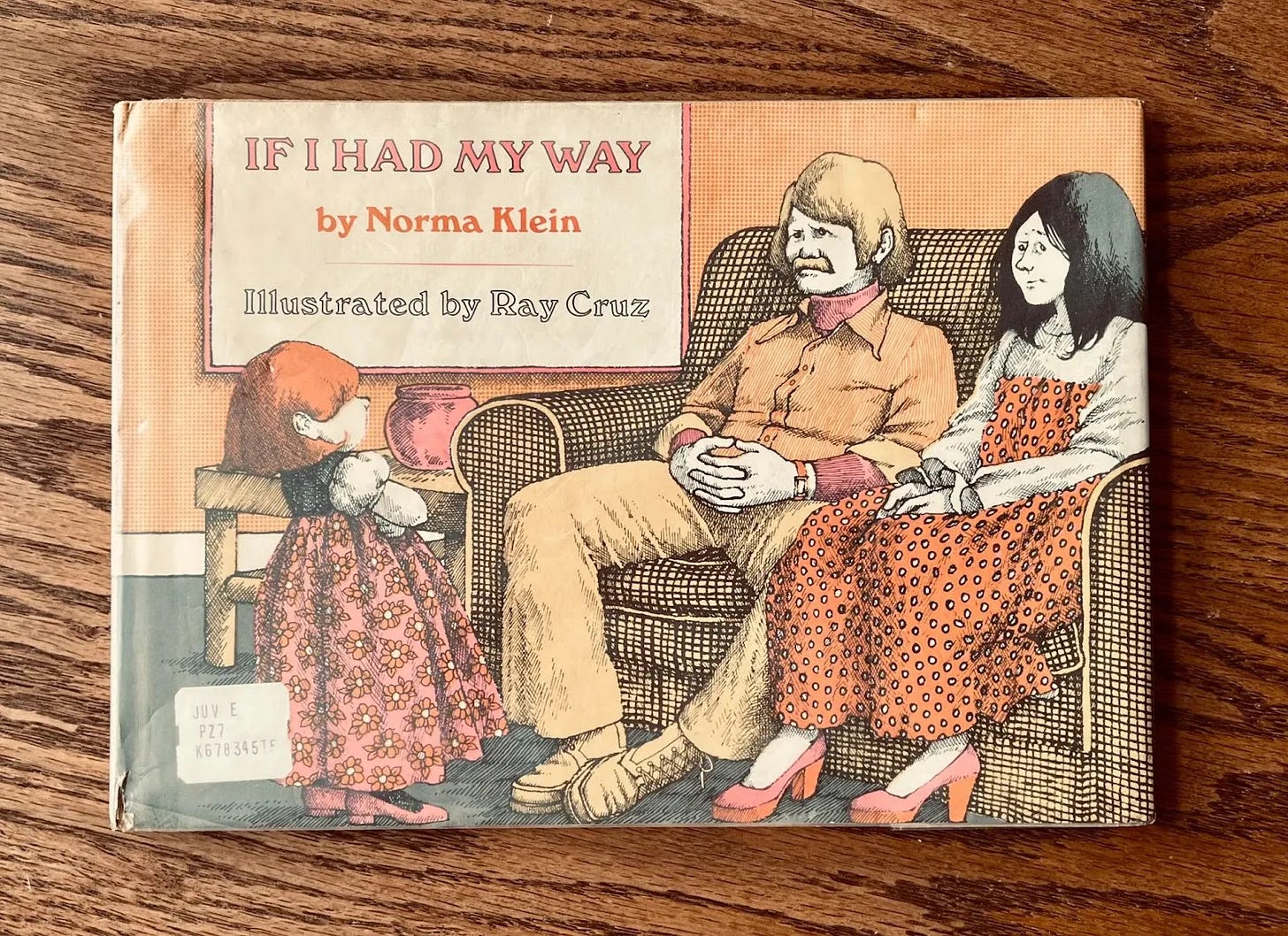

I wanted to be the grownup in charge, like in my favorite book: If I Had My Way by Norma Klein. I got it from a Chicago Public Library book sale. My dad was looking for records and sports magazines, but he gave me one dime to buy one book. I couldn’t read yet, but chose that one because the bodies drawn by Ray Cruz looked realistic and the little girl’s expressions looked like how I felt: annoyed.

Like the girl in the book, I wanted my way too. My way had to be better, I thought. Boomer parents didn’t seem to know what the hell they were doing. They did every don’t-do thing I was learning about: smoking, drinking and driving, not wearing seat belts, polluting, name calling, hitting. They even needed the TV set to remind them they had kids in the PSA: “Do you know where your children are?”

Being a “brat” made more sense than obedient, especially with my dad. I never listened to him. As I grew older, I walked out and hung up, even called the police on him once. I told him to F-off, many times. But I was also the one dad didn’t hit. I ended up feeling more guilty than brave.

The guilt made me feel like I shouldn’t have been born. The fear made me strive for perfection at school. But no matter how hard I tried not to care about my dad, deep down I never stopped wanting his love and approval. And I despised myself for that.

Feeling badgered by past family trauma

Last year, I wrote about my healing process after dad died in a Jumble & Flow piece, “Feeling badgered by past family trauma.”

Shortly before my dad died, he told my brother he felt like people misunderstood him. I’m sure it must’ve been hard having a mismatch between how he acted and how he felt. Maybe his brain worked differently. Maybe he processed emotions differently. I’ll never really know.

I’m sure my dad’s traumatic early life experiences contributed to his erratic behavior too. Seeing his sister get killed by a hit-and-run truck when he was three. And growing up amidst vicious arguments between his parents — the closest thing I’ve seen IRL to the ones in the Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf movie. Knowing this helps me empathize with my dad, though it still doesn’t excuse his behavior.

If my dad was simply aware that he was unaware of other people’s feelings, there’d still be problems, but I think a lot of pain could’ve been avoided — on all sides. Maybe then he’d have felt safe enough to let go of his Bucky Badger persona, and say the loving things he was only able to write. Or maybe just not be so mean.

But the bigger takeaway for me in the mourning process was becoming more introspective and honest about my own feelings and shortcomings. I knew if I didn’t continuously work on this, I’d end up like him and in my own way: hurting other people and not even knowing it.

3 ways my dad showed me he loved me

I’ll never forget — or excuse — my dad’s other side, but it doesn’t mean I can’t remember his loving side too. This Father’s Day, these are the stories I’m remembering.

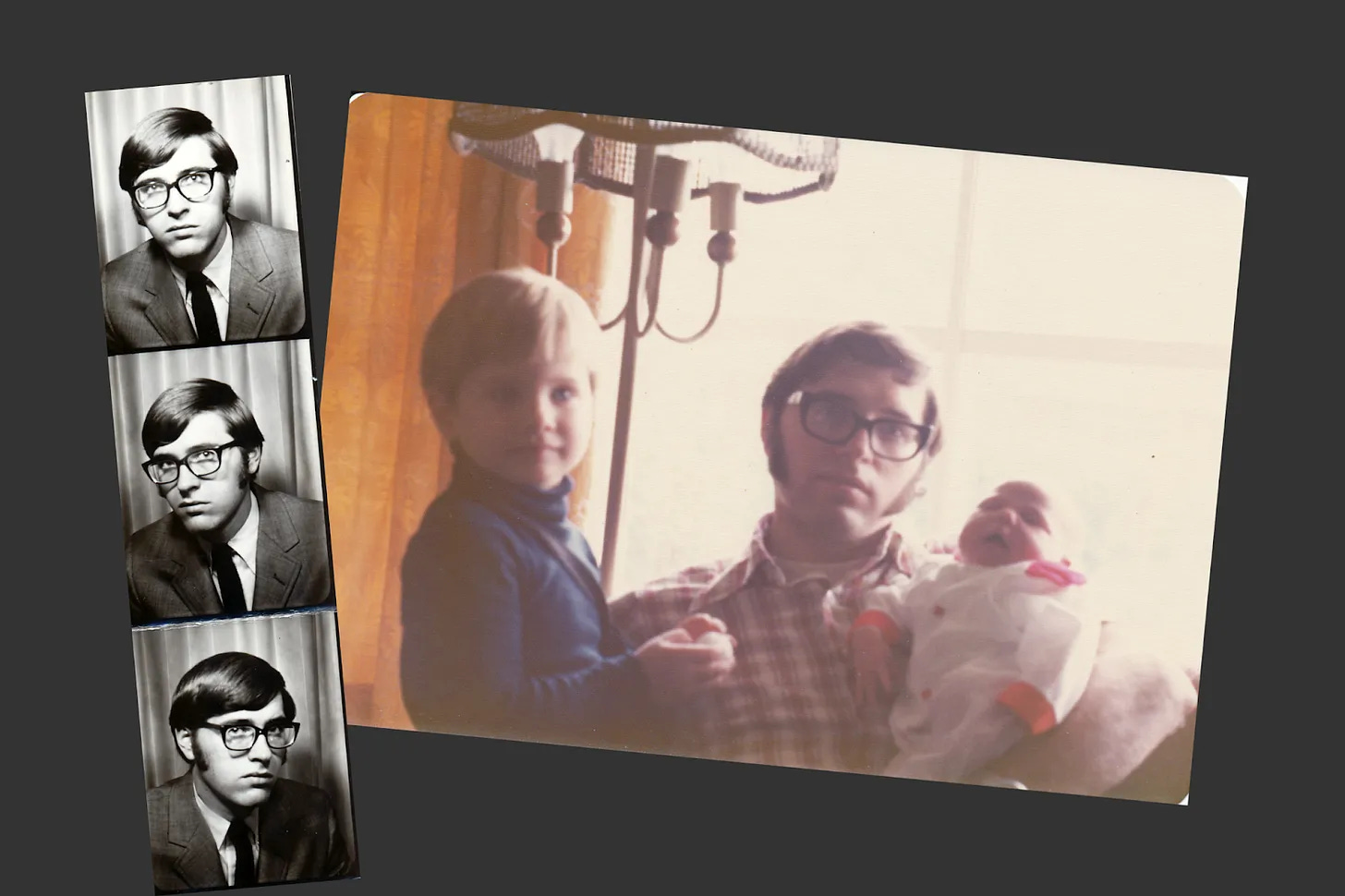

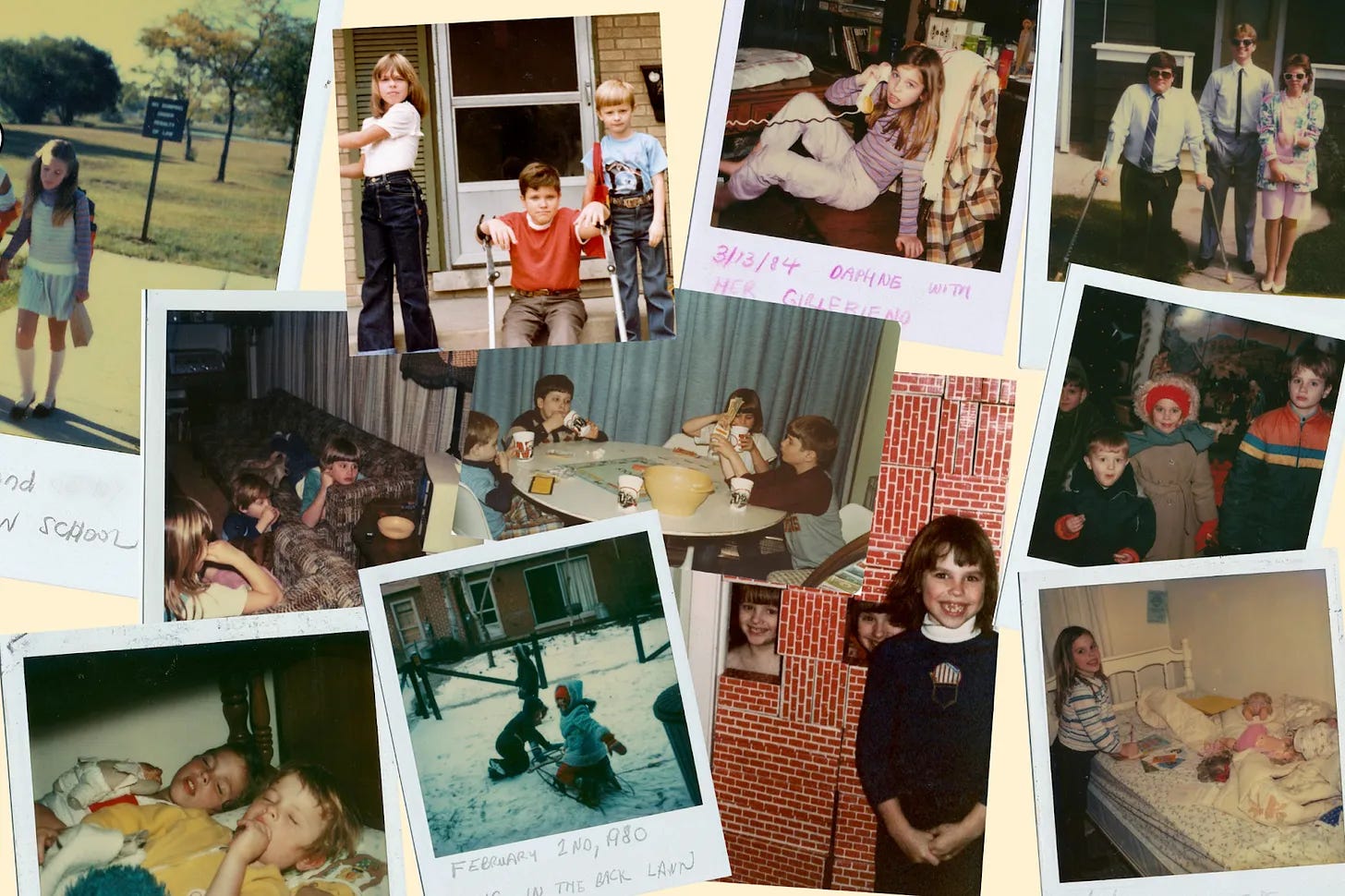

My dad took a ton of pictures of me and my brothers

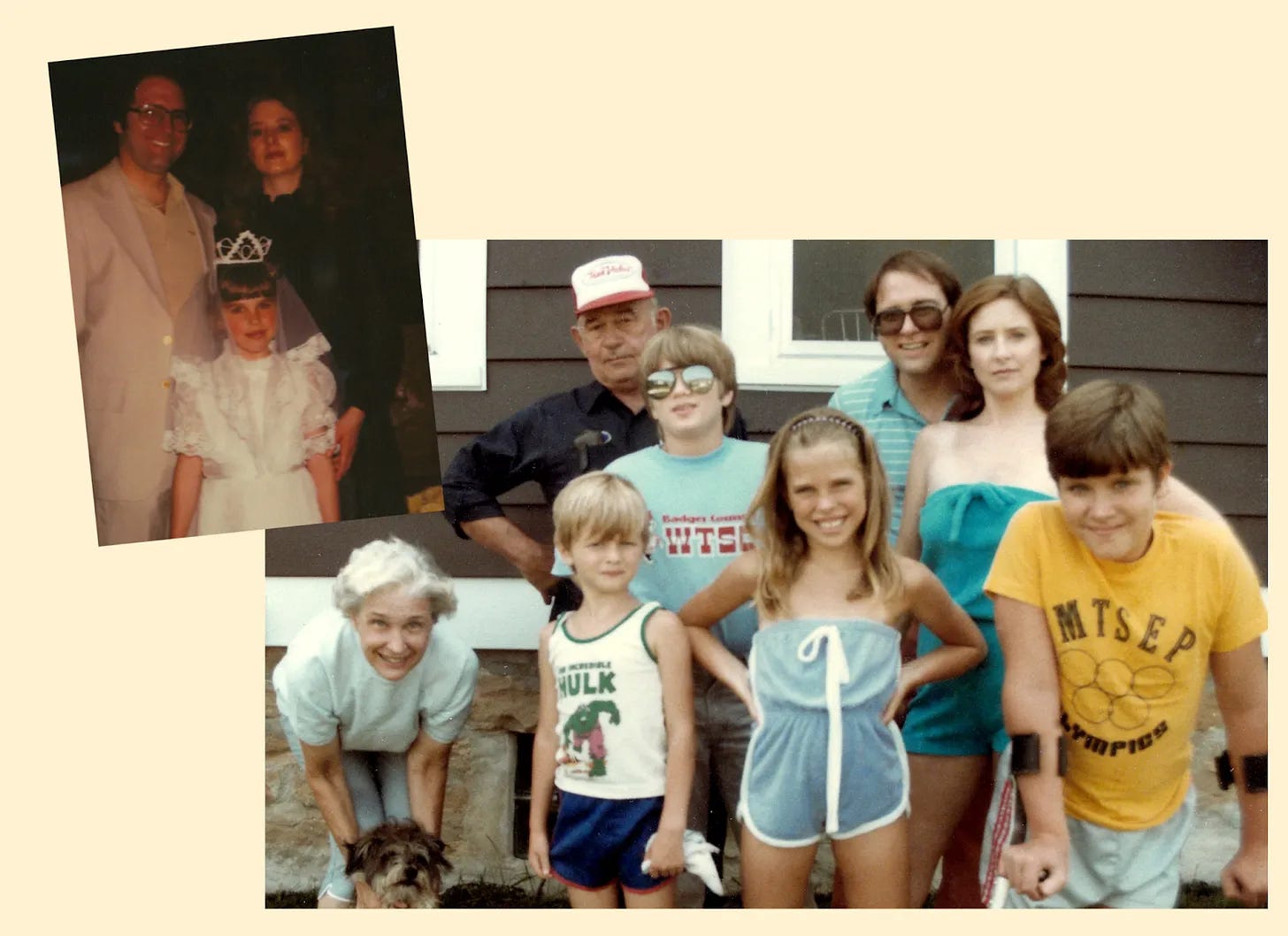

Back in the day when photos were film-based, and fewer pictures were taken, I love that my dad captured random everyday moments like these. After he died in 2008, I had tons of pictures that ended up with me to scan and share with everyone.

The sheer number of photos he took of me and my brothers — photos he captioned and clearly treasured — helped me feel his love. He took photos of me walking to school (I was so embarrassed), watching TV or playing with my brothers, talking on the phone with a friend, and even sleeping.

Six months before dad died he sent me a postcard, one of his favorite ways to save a few pennies. He wrote that his greatest regret in life was missing out being there to watch us grow up and develop. I cried as I read it. I’ve always loved my dad. But I’ve never wanted to love someone who didn’t love me back. I thought maybe I was wrong about dad. I need to tell him how sorry I am. And I planned to do just that.

The next time we talked on the phone, I started losing my nerve as soon as I noticed dad was in his usual cocky mood. But just when I was about to, he asked me why I never liked playing sports. “I have more of a dancer’s body,” I told him. Since I was three years old, I knew that was how my body liked to move. He laughed meanly and said “Who told you that?”

What a jerk, I thought, losing any desire to say anything nice to him. I cried again after we hung up, because I really wanted to have a heartfelt conversation with him.

I don’t regret not saying anything then, even knowing I never ended up having the chance. The word “sorry” loses all meaning if it’s forced out. But I do regret tossing the postcard out after our call, because I know what he wrote was truly how he felt.

I wasn’t ready to accept his love then because I was still too hurt. It’s easier now because I know he mean-talked to me the way he was talked to as a kid. The same way he probably talked to himself. It had nothing to do with me.

Just because my dad couldn’t show love for me in the way I wanted, doesn’t mean I can’t feel the love he had for me, in the ways he was able to show it.

My dad bought me a Cabbage Patch Kid in 1983

Rarely did my dad buy me anything I wanted, or could even use. Presents had thick-layers of marked-down stickers. Nothing wrong with a good deal, but the stuff usually didn’t even fit. When I got something good, it was usually after days of awkwardly hearing the rumblings of an argument from my mom trying to convince him to buy it for me.

But one day, at the start of my fourth grade year, just a bit after my 9th birthday, my dad came home from work with a big surprise. A Cabbage Patch Kid, new in the box! He must have gotten it from the JCPenney store where he worked, I thought, since I knew they were really hard to get.

But I held back my excitement. I remembered the last “surprise” my dad got for me: Michael Jackson’s Thriller album. The one he wouldn’t let me open and hear play. The one that would’ve brought me exponential joy two years before I had a boombox and could make mix-tapes.

My dad had this weird compulsion to get stuff, but never use it. He got the status-y feeling just by having it, but avoided any monetary loss that’d come from using it.

This time was different. He did let me open the package — after taking a picture. And he even let me take my Cabbage Patch to school the next day. The first thing I did though was change her name from 70s-sounding Marsha to much-cooler Kirstin.

But my Cabbage Patch interest ended pretty quickly. It wasn’t much fun playing with her because my friends didn’t have one. And soon, I tossed ALL my toys aside. Forget being a kid, or even an adult, being a teenager seemed even better — early GenX teen culture was sooo alluring, and a relief from the always-boomer pop culture.

Recently, I’ve thought about how my dad must’ve felt, seeing me toss the doll aside just as he was losing everything important. Dad was blindsided that fall when mom filed for divorce. But quickly his win-at-all-costs instinct set in. Our family entered a yearlong hellish divorce process, all while living together in our two-bedroom townhome. From that point on I always sided with my mom.

A few months ago, I found out something new. My mom told me how dad spent weeks looking for my Cabbage Patch, driving around store to store. It was supposed to be for my birthday, but it took him a few weeks longer. She said dad was so excited when he finally found one.

No one ever told me dad got my Cabbage Patch easily from his work. But I must’ve assumed that because it fit the narrative: my dad was selfish. He wouldn’t go to great lengths for me or anyone else. This made me wonder: what else do I have wrong? How has being so attached to the she-said side, prevented me from seeing the full picture?

I’m learning I need to leave spaces open for some things I might have wrong, don’t know, or can’t understand. And from that place, it’s easier to stay more open to love, including my dad’s.

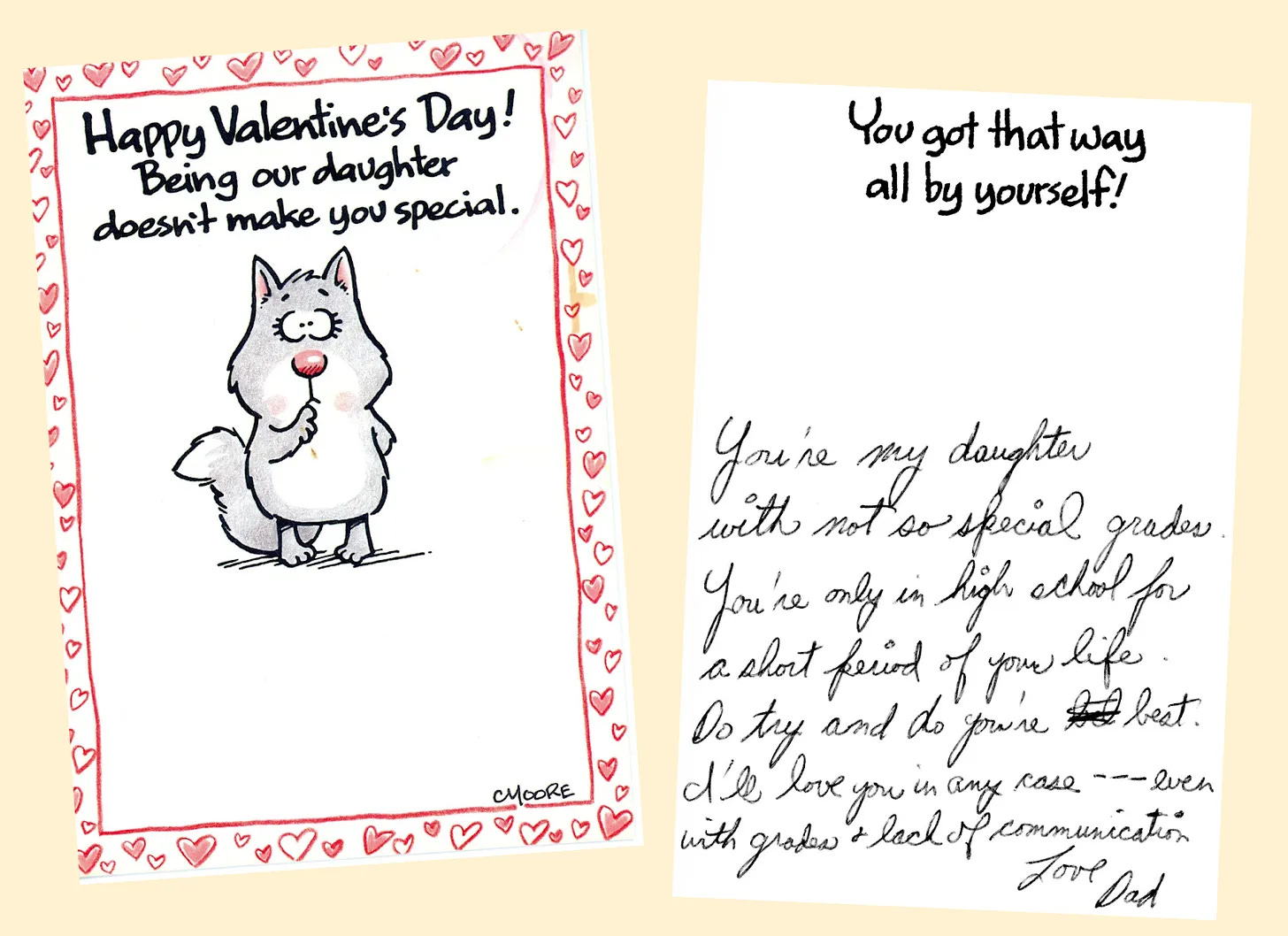

My dad never stopped trying to connect with me

I keep this Valentine’s Day card from my dad in my nightstand drawer. “You’re my daughter with not so special grades. You’re only in high school for a short period of your life. Do try and do you’re best,” he wrote to me in 1990 when I was 15.

Dad had no clue what happened to the straight-A cheerleader who listened to Debbie Gibson and chose to wear plaid. Early on in high school, I reached the point where keeping a facade of normal felt impossible and I wanted friends who felt like I did: life sucks, so why try? In my choices of cafeteria tables, I found this with the burnouts and my glam-metal friends.

Dad was recently transferred to an out-of-state JCPenneys and only heard some of what was going on with me — mostly things he was legally required to know. Like how I spent my Saturdays in detention, sitting socially distanced in a nearly empty high school cafeteria. Or that I was arrested with my 14-year-old friends for stealing lingerie at a Venture store, the one with the diagonal black-and-white striped logo in walking distance from my home.

And even though dad loved playing his Mötley Crue’s Girls, Girls, Girls tape in the car, he wasn’t happy when he heard I was going to their concerts and dating guys with long hair. He was hoping my first boyfriend would be a jock.

My dad’s advice was of no help when I was 15. Or at 16 during an even bigger crisis period. But at 17, the words “I’ll love you in any case” mattered when I was trying to find some way forward to somewhere better.

I know my dad loved me because he never gave up trying to connect. It’s a reminder to me that trying still matters, even if imperfect. Even if it doesn’t fix anything. Reach out and do what you can. Don’t overthink it. Just do it.

Final thoughts: self-awareness is sooo important

My First Holy Communion picture is the only one I have of just me with both my parents. The other photo is the last one of my family all together before the divorce. Both pictures look so familiar — my mom, clearly unhappy, and my dad, clearly clueless.

“You can only be as intimate with another person as you are with yourself” — that quote from Kate Murphy’s You’re Not Listening book is one I love. From my experience, it’s spot-on, and it’s why I write things like this. By understanding and owning my life stories, I can avoid pulling others into old storylines, maybe hurting them in the process.

So yes, I can accept my dad’s love, but only as part of a larger story. The loving part of my relationship with dad was small, and never enough. But the love has grown in my heart, and has become enough for me and to share.

This post is syndicated from Daphne’s amazing Substack, Daphne Discloses.

All images are courtesy of Daphne Berryhill.

Daphne Berryhill is a clinical pharmacist and writer. Currently, she holds a position as an oncology specialty pharmacist and freelance writer for GoodRx Health. She also writes for Musical Pathways and on her Substack, Daphne Discloses. Writing topics include pharmacy, parenting, and cultural changes. Daphne firmly believes writing is one of the best forms of therapy available! She lives in Madison, WI, with her husband of 29 years and their four children.