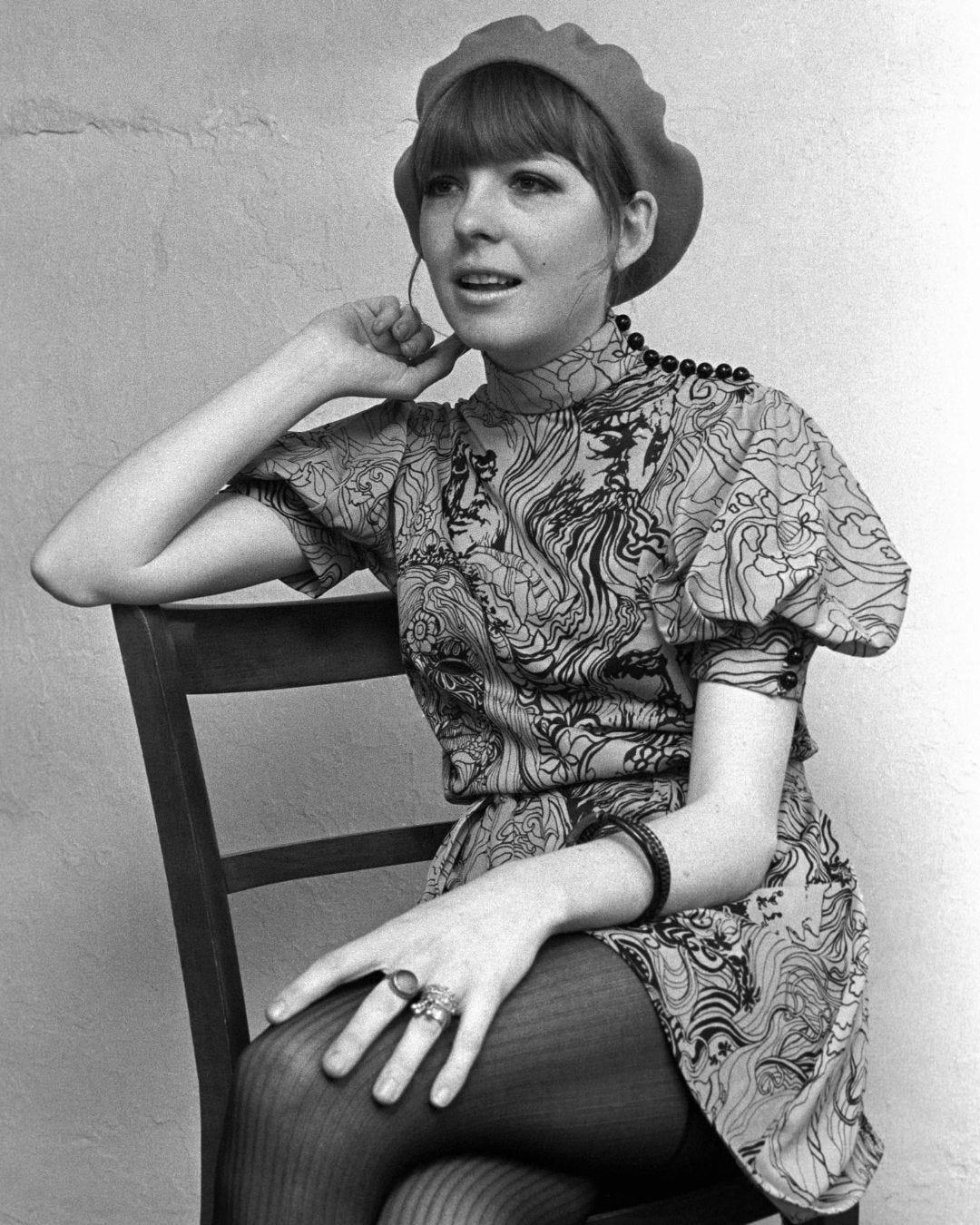

We can’t believe you’re gone. Rest in power, Diane Keaton.

“You can buy them in bulk, honey.”

The woman behind the Dairy Queen counter pointed to the pre-made ice cream sandwiches in the fridge. Oh, my god. Did she know that I puked them up, too?

I was an unsuccessful bulimic — my binges surpassed my purges — and I was overweight, having gained 30 pounds since I started college the year prior. The trauma from date rape (is the passive modifier “date” still used these days?) left my 19-year-old mind seeking control over my body. Food was an obvious choice to spike my dopamine and reclaim my power — although it took me years to realize that’s what I was doing.

I can’t remember the details of this time in my life with clarity, but my writing helps memories resurface — and I am reminded of how I could “see” again after the Dairy Queen herself shamed me to seek out Overeaters Anonymous (OA) meetings. (Despite its name, OA helps people recover from eating disorders like anorexia, bulimia, and of course, compulsive overeating.) It was as if a veil fell from my eyes — I saw the sky and the colors in the flowers: I wasn’t (as) consumed with food and weight and secrets and control.

What people don’t know — often including people suffering — is that eating disorders are a disease of the mind: An eating disorder is a serious, complex, mental health issue that affects someone’s emotional and physical health. And like being an alcoholic in recovery, being a bulimic in recovery is very much the same — there are triggers and maintenance, and it never really goes away.

When everyone and her sister (search “semaglutide” on TikTok to see for yourself) started taking Ozempic-like drugs for weight loss, those icky feelings of shame and control resurfaced — big time. Why do I feel this way again? I thought I was done with this bullshit.

Cue Australian writer Kerry Martin Millan who emailed me her pitch about the concerning trend of peri/menopausal-aged women (re)developing eating disorders. The timing couldn’t be more perfect personally, and like much of the stuff we MidstHers experience, if I felt this way — and if Kerry felt this way — likely you or another reader is going through it, too.

Find Kerry’s captivating piece below, and please know that if you’re in this headspace, too, you’re NOT alone.

Meno-rexia: The alarming trend of eating disorders during perimenopause and menopause

I always thought I was well past my adolescent eating disorder. But at 47, I started dieting intensely. Now I realise what might be prompting my preoccupation with calories and fat at this age.

Too old for eating disorders?

I found myself looking in the mirror again at 47, worrying about the changes in my physical appearance – the lines on my forehead, the weight that had accrued on my hips. Concerns about the perceived blandness of my physical features rose up within me like a tidal wave. Yet, I had forgotten about this stuff long ago. I immediately cast it off as a fluttering awareness of older age. I told myself to perk up and to stop the adolescent fantasy. I’m still on a diet, though, wondering why I care so much.

According to research, my fears aren’t just adolescent fantasies. As per the recovery blog, Eating Disorder Hope, a growing trend of older women, largely between 40 and 50 years old, at around 1 in 28 in the U.S., actively have eating disorders. The recovery centre also goes on to say that according to Kansas University research, 20% of middle-aged women in the U.S. possess body dissatisfaction.

Emmett R. Bishop, MD, a founding partner and medical director of adult services at the Eating Recovery Center in Denver, expounds on the obvious reasons for eating disorders at this age: bodily changes beset by hormonal fluctuations, weight gain, and changes in all over physical features that ensue feelings of a loss of control.

I’ve always thought that because my eating disorder was eons ago, I’m now immune. I was 13, with severe anorexia, weighing an unbelievable 35 kilograms at 167 centimetres [about 77 pounds at 5’6”]. But I’m wrong. Statistics say that I’m more likely to develop an eating disorder in middle age because I once had a teen eating disorder.

A global obsession with age could be responsible for midlife eating disorders

I also can’t help to think that the catalyst for eating disorders in midlife is much deeper than weight. This time, I’m right. Women are also living in a time of weaponized language about age – to add, in a global context. Anti-aging rhetoric is no more prevalent than in the world of cosmetics and celebrity. Converted in the mind of the anorexic, where loss of control shapes their response, even anti-aging is brutally persuasive.

“Reducing visible aging and fine lines,” chants a L’Oreal ad for anti-aging cream. “Age-proof,” “age-defying,” and many anti-aging epithets describe the ways in which women are obliged to fend off the inevitable. Even the very word “concealer,” used to describe the job of foundation, is about “hiding” flaws and “concealing” ugliness.

If it’s not Andie Macdowell’s grey hair that’s problematic, it’s Meg Ryan’s alleged gaudy cosmetic surgery or Sarah Jessica Parker’s marked aging process. In truthful defiance, she retorts in US Magazine, “I have no choice. What am I going to do about it? Stop aging?”

It goes even further for Jessica Parker, who was touted the “No. 1 Unsexiest Woman Alive” by Maxim magazine. She is reputed as saying the poll was “brutal” and it even affected her husband Matthew Broderick.

But it’s the message to others that’s shattering, that says unattainable beauty leaves you open to social vigilance and vitriol. Although that comment could be politically motivated, perhaps where another didn’t get a movie part or Jessica Parker riled someone in some way. Who knows?

Seeking writing submissions about eating disorders

“This Is Not Your Mother’s Eating Disorder” is an anthology organized by Founding MidstHer Amie Newman, who is seeking personal essays, poems, visual art expression, and cultural critiques by midlife and older women who have experienced an eating disorder in adulthood.

1,000–3,000 words for personal essays and interviews; 100–200 words for poems. Learn more and submit here. If you have questions, please email amie.newman@gmail.com.