Nothing compares 2 U: RIP Sinead O’Connor

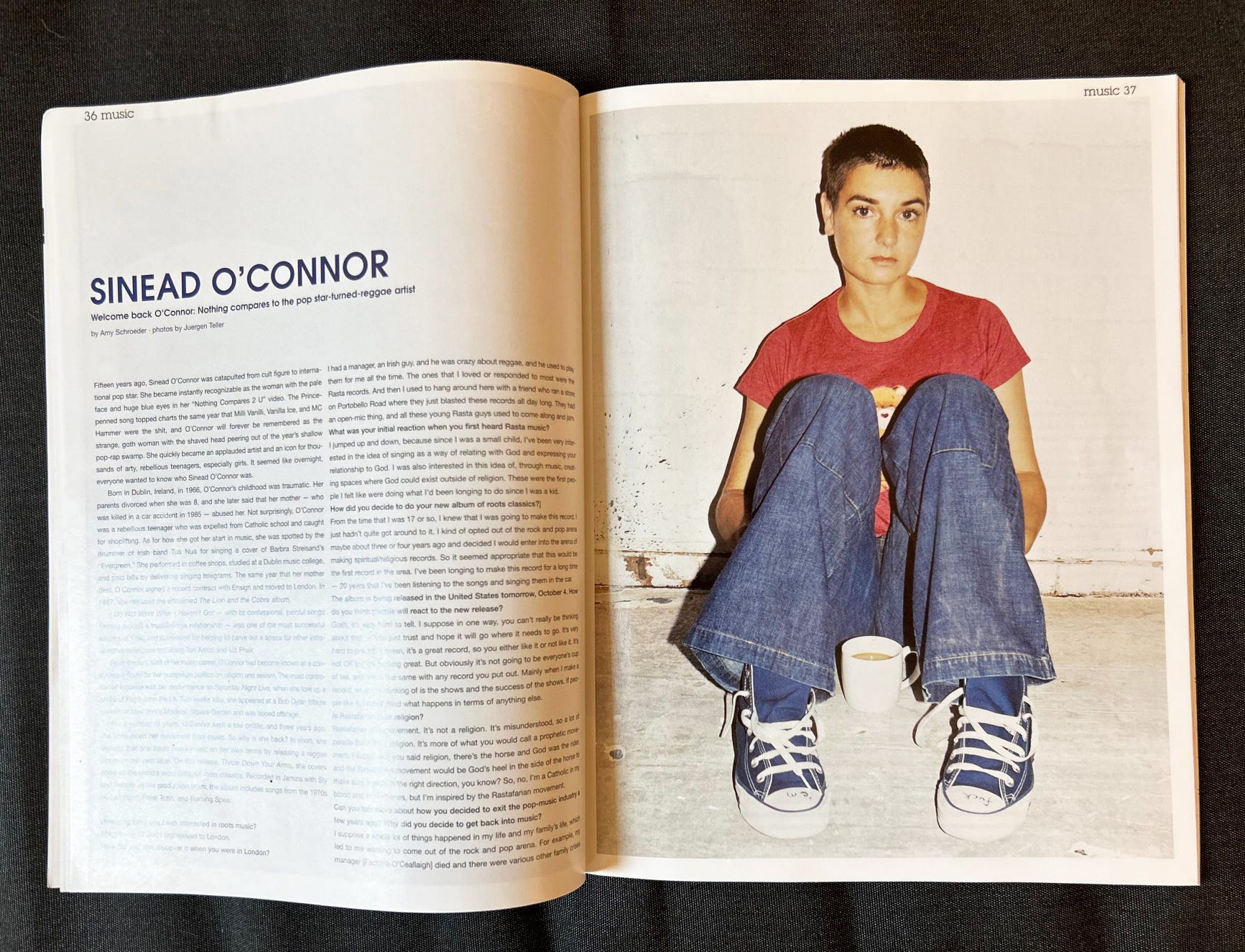

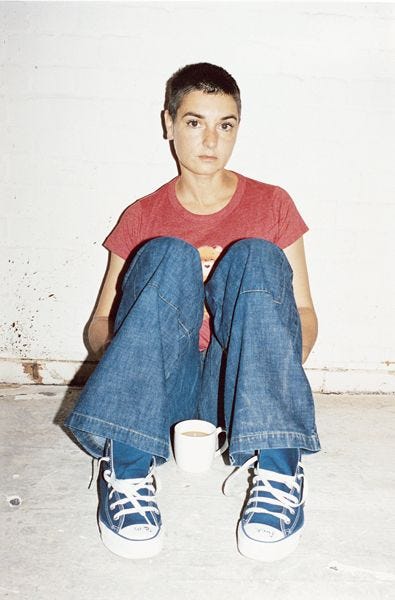

In this 2005 interview, the incomparable songstress and activist talks about "fighting like a man," God's underemployment, and 50 Cent. By Amy Cuevas Schroeder • Photos by Juergen Teller.

This interview was originally published in Venus Zine in 2005, titled “Welcome back O’Connor: Nothing compares to pop star-turned reggae artist Sinead O’Connor.”

In 1990, Sinead O’Connor was catapulted from cult figure to international pop star. She became instantly recognizable as the saintly face with huge blue eyes in her “Nothing Compares 2 U” video. The Prince-penned song topped charts the same year that Milli Vanilli, Vanilla Ice, and MC Hammer were the shit, and O’Connor will forever be remembered as the strange, goth woman with a shaved head peering out of the year’s shallow pop-rap swamp. O’Connor quickly became an applauded artist and an icon for millions of arty, rebellious teenagers. It seemed like overnight, everyone wanted to know who Sinead O’Connor was.

Born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1966, O’Connor’s childhood was traumatic. Her parents divorced when she was 8, and she later said that her mother — who was killed in a car accident in 1985 — abused her. Not surprisingly, O’Connor was a rebellious teenager who was expelled from Catholic school and got caught shoplifting. As for her start in music, she was spotted by the drummer of Irish band Tua Nua for singing a cover of Barbra Streisand’s “Evergreen.” O’Connor performed in coffee shops, studied at a Dublin music college, and paid bills by delivering singing telegrams. The same year that her mother died, O’Connor signed a record contract with Ensign and moved to London. In 1987, she released the acclaimed Lion and the Cobra album.

I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got – with its confessional, painful songs circling around a troublesome relationship – was one of the most successful albums of 1990 and is credited for helping to carve out a space for other introspective musicians including Tori Amos and Liz Phair.

From the very start of her music career, O’Connor had become known as a controversial figure for her outspoken politics on religion and sexism. The most controversial instance was her performance on Saturday Night Live, when she tore up a photo of Pope John Paul II. Two weeks later, she appeared at a Bob Dylan tribute concert at New York’s Madison Square Garden and was booed offstage.

For a number of years, O’Connor kept a low profile, and in 2002, she announced her retirement from music. So why is she back? In short, she realized that she could make music on her own terms by releasing a reggae album on her own label. On this release, Throw Down Your Arms, she covers some of the world’s most beloved roots classics. Recorded in Jamaica with Sly and Robbie as her production team, the album includes songs from the 1970s by Lee Perry, Peter Tosh, and Burning Spear.

How long have you been interested in roots music?

Sinead O’Connor: Since I was 17 and I first moved to London.

How did you discover roots music when you were in London?

I had a manager, an Irish guy, and he was crazy about reggae, and used to play it for me all the time. The music I loved and responded to most were the Rasta records. And then I used to hang around here with a friend who ran a store on Portobello Road where they had just blasted these records all day long. They had an open-mic thing, and all these young Rasta guys used to come along and jam.

What was your initial reaction when you first heard Rasta?

I jumped up and down because since I was a small child, I’ve been very interested in the idea of singing as a way of relating with God and expressing your relationship to God. I was also interested in this idea of, through music, creating spaces where God could exist outside of religion. These were the first people I felt like were doing what I’d been longing to do since I was a kid.

How did you decide to do your new album of roots classics?

From the time that I was 17 or so, I knew that I was going to make this record. I just hadn’t quite got around to it. I kind of opted out of the rock and pop arena maybe three or four years ago and decided I would enter into the arena of making spiritual/religious records. So it seemed appropriate that this would be the first record in the arena. I’ve been longing to make this record for a long time — 20 years that I’ve been listening to the songs and singing them in the car.

Your album is being released in the U.S. tomorrow, October 4, 2005. How do you think people will react?

Gosh, it’s very hard to tell. I suppose in one way, you can’t really be thinking about that — you just trust and hope it will go where it needs to go. It’s very hard to predict. I mean, it’s a great record, so you either like it or not. It’s not OK or it’s fucking great. But obviously, it’s not going to be everyone’s cup of tea, and that’s the same with any record you put out. Mainly when I make a record, what I’m thinking of is the shows and the success of the shows. If people like it, I don’t mind what happens in terms of anything else.

Is Rastafarian your religion?

Rastafarian is a movement. It’s not a religion. It’s misunderstood, so a lot of people think it’s a religion. It’s more what you would call a prophetic movement. I suppose if you said religion, there’s the horse and God was the rider, and the Rastafarian movement would be God’s heel in the side of the horse to make sure it goes in the right direction, you know? So, no, I’m Catholic in my blood and my bones, but I’m inspired by the Rastafarian movement.

How did you decide to exit the pop-music industry a few years ago, only to return to music?

I suppose a whole lot of things happened in my life and my family’s life, which led me to wanting to come out of the rock and pop arena. For example, my manager, Fachtna Ó Ceallaigh, died and there were various other family crises that had to be focused upon. I think it was 17 or 18 years that I was in rock and pop, and I really felt like a square peg in a round hole, which I think is a very kind way of putting the experience that I actually had in that arena. It was extremely stressful and strange. I wanted to opt out of that arena, and my feeling at the time was that I would never have anything to do with singing again. I didn’t even sing in the bath for three years.

But then I began to examine the ways that I could sing in a religious arena and I looked at every kind of crazy way that a person might do that. Would I sing in churches for a living? Would I sing at funerals? Would I make a living singing Gregorian chants at funerals or what would I do?

After a while, If you're not acknowledging a huge part of you, which is your creative part, you can begin to get quite depressed. So I needed to do something with singing, but not in that arena. Finally it obviously occurred that I could actually make records for a religious arena and writing songs. Apart from Christian rock people, nobody really seems to write religious songs, hymns, or whatever — or “hers” as I like to call them.

“Apart from Christian rock people, nobody really seems to write religious songs, hymns, or whatever — or “hers” as I like to call them.”

— Sinead O’Connor

My kids got tired of my cooking as well. I’m a single mother with three children — I have an 18-year-old, a 10-year-old, and an 18-month-year-old. I got kind of worn out. The trouble is, if you do what I do for a living, your work is your social life. I got a bit of an occupational hazard when you have children and you can be so much in your house that you don’t meet anyone. I had to try to get the balance correct here as well — where I was there as much as I want to be for my children but also for myself. To do enough work so I don’t lose Sinead. They did get really sick of my cooking, too. If I don’t burn the house down, I certainly burned dinner.

I think of you as an incredibly strong and activist-oriented woman who stood up to so many industry pressures over the years. Where do you think your strength comes from?

That’s a very good question. I’m not sure that I know the answer. I suppose there are different places that it comes from. I think that I’m Irish is a huge part to play in it. For example, nearly every TV show in Ireland that is popular involves the public phoning in and expressing their opinion. We’re very opinionated people and we’re brought up to know that we have the right to raise our hand and open our mouth at any time.

Also, I have huge faith in whatever you want to call “God.” I’m also slightly crazy, which helps — you have to be slightly crazy. I’ve been inspired by people who are similarly crazy and determined to stand up for what is not considered to be the norm. Also, I’m very mischievous and I’m very male. What I mean by that is that I fight like a man. I’ll be sweet and loving, but I fight like a man — I suppose because I’ve had to. Sometimes, the softer you are, the harder you have to fight. I’m a bit of a crazy bitch and it helps. But I like to fight.

“I’m very mischievous and I’m very male. What I mean by that is that I fight like a man. I’ll be sweet and loving, but I fight like a man — I suppose because I’ve had to. Sometimes, the softer you are, the harder you have to fight. I’m a bit of a crazy bitch and it helps. But I like to fight.”

— Sinead O’Connor

What are you most concerned about with the world today?

God is very underemployed in the world we’re all living in. To put it as compassionately as I can, I feel that the entire world appears to be paying for what a few people did on September 11. Whether it’s a threat from a Muslim extremist or whatever, the result of September 11 is the world is a far more terrorized and terrified place to be than it was before that day. It seems to me like the whole world is being punished for what a few people did and, of course, it’s quite right that those few people should fucking never see the light of day for what they did. What concerns me is that the entire world — especially the children — are terrorized by this war that is called a “War on Terror,” but in fact, creates more terror than there was before.

In this day and age, we need to learn that war is not the solution to anything. We have to ask ourselves, “Well, what is the solution?” And to me, it is this idea of I should be employing God.” Not necessarily true religion, but there is something out there that responds to the human voice, which we can employ which will fix things very quickly if we believe in it. I think religion has done an awful lot to make people think there is no God, and that’s what concerns me most, because that renders people powerless.

That’s what would concern me as an artist, and every other way. We have to let people know that it doesn’t matter if you're sitting on the toilet, if you invoke the universe or nature or whatever you call God to actually help the world. It concerns me that God is under-employed and we’re all living in Hell. Even George Bush doesn’t seem to believe in God. Everyone seems to need help. We’re victims of this kind of conditioning for thousands of years that war is how you solve things. Then we’re too proud to say we were wrong and we’re sorry. Nobody is saying the word “love.” Nobody is saying, “Why don’t we try to sort this out with love.”

What do you teach your children about the world?

I teach them to treat people as they want to be treated. I teach them if they’re walking behind old people to put a wide berth behind old people so that they don’t become frightened by you. If you walk fast behind old people, it frightens them. To respect old people and be gentle around them. And to love each other — I made my kids each other’s godparents and I kind of drill it into them that they’re never to fall out, so they’re very affectionate. My 10-year-old and 18-year-old snuggle. Also, I try to boost their self-esteem without thinking that someone is less than you. I don’t beat religion into them or anything, but I do let them know that there is a god who lives and responds. And I also teach them to get me chocolate.

How do you feel about today’s popular music? What do you like and dislike?

I’m bored with girl bands and boy bands and that whole pop-idol thing. I just think it’s evil, all that pop-idol business. I really think it’s horrible. To employ a Michael Jackson phrase, “It’s devilish, very devilish.” This kind of worship of fame and the humiliation of these people who come on and are willing to make themselves vulnerable. I don’t like the way the judges treat people on those shows. So it seems some of those bands have kind of infiltrated the music scene and it’s yucky. What do I like? I like 50 Cent; my kids take over the TV and the radio and everything, to be fair, so I don’t really get to know what’s going on nowadays. All my 18-year-old is into is gangster rap, which is all very well, but I’m nearly 40.

How do you feel that your life is different now than when you were just starting out with your music career?

Gosh, I suppose in zillions of ways. It’d probably take 10 years to explain. I have three children now. Apparently, I’m a lot more wrinkled.

You’re releasing Throw Down Your Arms on your own record label, That’s Why There’s Chocolate and Vanilla. How long has the label been around, and why did you start it?

It has only been around for about six months. I named it what I named it because that was a saying of my old manager, the one who died. He used to say it all the time. When I would grumble and someone wasn’t thinking what I freaking think, he’d go, “That’s why there is chocolate and vanilla.” So I always figured if I start up a record company, that’s what I’d call it.

“If you’re going to leave your kids and work hard in blood, sweat, and tears to make a record, you’re not going to fucking give it to the record company. Fuck ‘em.”

— Sinead O’Connor

I decided I’d put this record out on my own label a) because you make more money that way and b) which I suppose is more important, is that it gives you creative freedom. You don’t have a record company interfering with the type of record you want to make. So if you want to make a record of cow noises, you can. Why would you sell your creativity to the mainstream industry with its top payment to any artist 18%, where if I put it out on my own label, I can actually make 90% if I want to, or I can do joint-venture deals where I can make 50%, which is what I do.

If you’re going to leave your kids and work hard in blood, sweat, and tears to make a record, you’re not going to fucking give it to the record company. Fuck ‘em.

Do you plan to sign any other artists on your label?

No, absolutely no. Because then I would become “one of them.”

Amy Cuevas Schroeder is the founder of The Midst and Jumble & Flow. She’s also a parent of twin girls who’s navigating the rollercoaster of midlife and perimenopause. In addition to The Midst she works full time as editorial director for Unusual Ventures. She’s previously worked and written for Etsy, Minted, HarperCollins, West Elm, NYLON, and Pitchfork. She started her first business, Venus Zine, about women in music and DIY culture, as a freshman at Michigan State University.

Follow Amy @thevenuslady on Instagram.